My Papi Had a Motorcycle Parte Dos

Second Part. Probably just one or two more posts left about this.

This essay is not about the dad in Gabi, a Girl in Pieces. This essay is about the dad in My Papi Has a Motorcycle.

Like I said, that doesn’t matter because they are the same dad.

****

My father has always worked with his hands. In Sinaloa, where he’s from, and here in the U.S. He picked tomatoes, worked on a cattle farm, built RVs, as a mechanic, and as a cabinet installer. I don’t remember what he was helping me with recently but it required a nail being pushed into a piece of wood. Maybe it was the book cases he made and it was the bracket for the shelves? Anyway, he saw me grabbing the hammer and said, “No puedes con las manos?” And I unsuccessfully tried to push it in. “No.” So he took it from me and said, “Así, con los dedos.” His thick calloused thumb pushing the metal through the wood as if it was a hot spoon slicing manteca. “Es que tus manos estan muy suavecitas. Muy soft.” He laughed.

He wasn’t wrong. My hands for the most part are soft. My job now is making up stories and while that requires typing, it’s not enough to turn my fingertips into hammers. I’ve had many jobs but none have required my skin grow thicker skin, at least not literally. My first “real” job was McDonald’s. I was there for the Beanie Baby craze. Before that though, I made tacky home decor with my glue gun and lace I’d buy at the swap meet. Remember those burgundy lace toilet paper holders our tias had in their bathrooms? Where do you think they got it from? Aquí meregues. I would make them and hustle them to my mom’s friends or the moms at the bus stop. I’d save some money and then invest in more materials. Or in selling candy at school until someone snitched and Ms. Ericson our health teacher made a general blanket statement about how selling candy was against school rules.

Some of my other jobs were book seller and barista but I’ve worked mostly in education.

But my dad, my dad has been someone’s hammer and wheelbarrow, someone’s drill and saw, someone’s sit two hours there and two hours back in traffic, someone’s up and down stairs with cabinets on your back for four decades. All without knowing how to read and not speaking English.

****

The last time I was in Sinaloa was when I was a kid. The trip itself was an adventure that involved a train on fire and a bus without breaks, and I’ll share that some other time.

The year is 1992, let’s say. It’s hot and humid because it’s summer and we’re there on vacation visiting my dad’s family who live on an ejido. Across the street from my abuelitos was the school and not far from there some bulls and cows grazing, unfenced. There were only dirt roads that cars and horses and donkeys shared. It was very different from home. I loved it. I loved the heat, helping my abuelita at her store, going fishing with my cousins, the mangos and tamarindo in the backyard. The stuff that was fun. I didn’t see poverty or the cartels or lack of opportunities. I wouldn’t see that until much later.

This was not where my dad was born though. He was born on a rancho near Culiacán where he remembers motorcycles as the most common type of transportation and rarely remembers a working car. It was rural and there was poverty, and folks had a lot more to worry about than education. He says there wasn’t a regular teacher around and when there was my grandparents didn’t really push him to go to school, so he didn’t. Instead he’d go play with his friends or work and he never learned to read.

When he came to the U.S. as a young man in his late teens, the jobs available to him didn’t require that he be literate or bilingual. They were jobs that required his body, his strength, his stamina, his hunger and nothing more.

When the work did require writing I was usually the one who handled it. I filled out his time sheets; each one had to have the lot number and what he did at each job site. For example: “June 25, 1991. KB Homes Lot #34 Model 3: Installed the cabinets in all three bathrooms. Installed the island and all doors. Installed molding and baseboards. Lot #33 Finished kitchen and butler pantry.” I logged his labor and was always amazed that my dad did all those things in one day. The timesheets were due each Friday and my dad would usually wait until Thursday night and so I’d sit there with all the pressure of his paycheck weighing on me as he tried to recall, eyes closed and his fingers pointing at the invisible homes in front of us. I worried I’d write something wrong and my dad wouldn’t get paid. I never told him that, though. I was the eldest and had responsibilities.

Having a father who is illiterate while I get paid to write books is a mind fuck. There is guilt I wrestle with about the “Why do I get to do this and my parents don’t? Why did I get to go school and my dad got to fuck up his body?” I’ve worked on it in therapy.

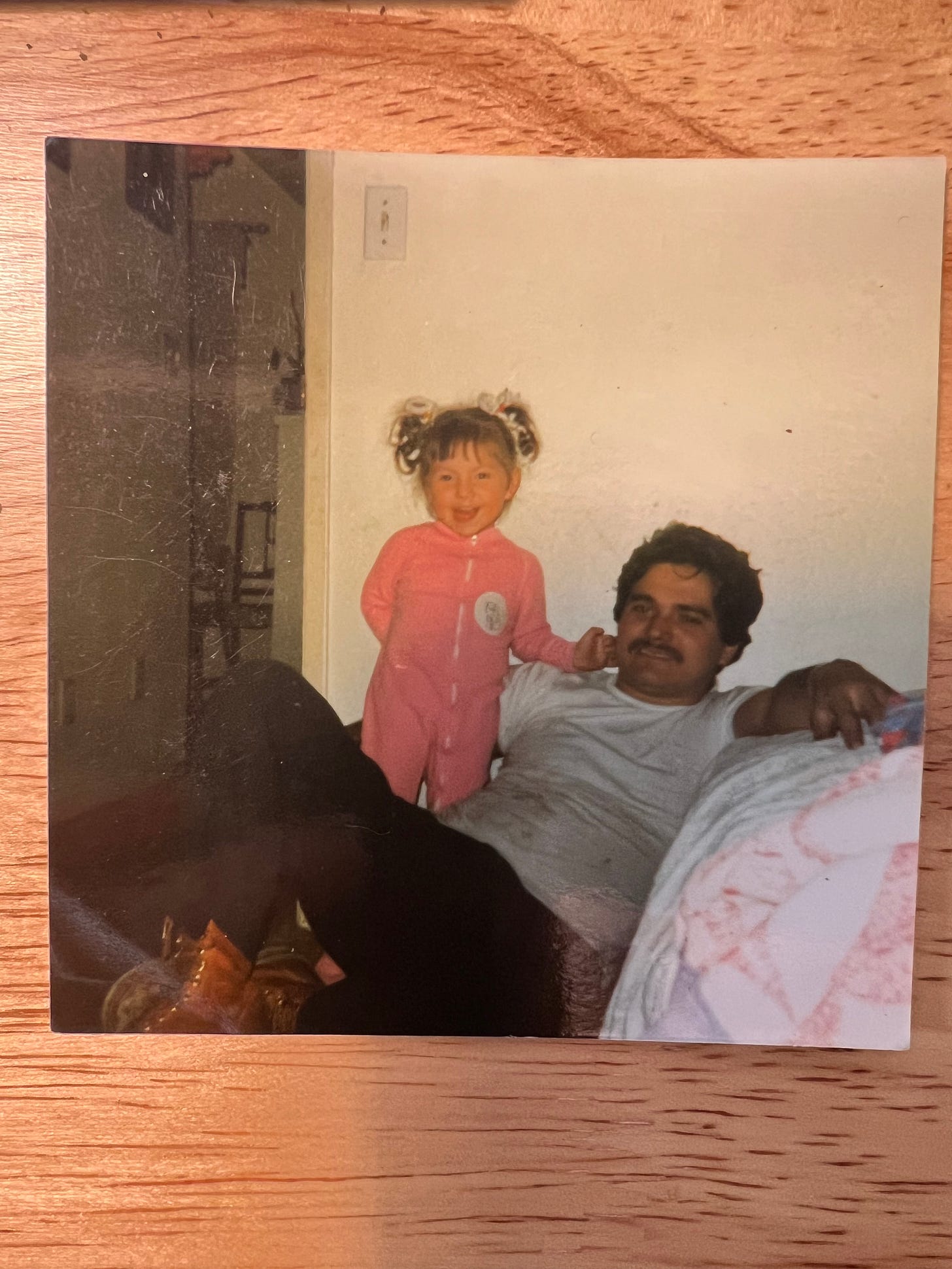

I have always been a reader and when I was learning to read my mom would be the one to read with me. My dad obviously couldn’t but that didn’t mean that I didn’t want him to. I remember trying to “teach” him as early as preschool or kinder with my Berenstain Bears books but he had no interest in Brother or Sister Bear. I dreamt about sitting on the couch and my dad reading to me so much as a little kid, as much as I dreamt about sharing books with my dad as a young person. My dad is a critical thinker. We’ve had discussions about societal issues and politics and length before. He is a smart and creative man who cannot read and in this country that means you cannot move up at work and you are relegated to less-than. We’ve never talked about it but I’m sure it takes a toll on a person’s sense of self. It would take the idea of being able to read to his grandchildren to really get him motivated.

I can only talk about this now because when interviewed him for the Harley-Davidson exhibit he talked about it and it’s up for every visitor to the exhibit to see.

My dad is 62 and for the first time he is writing notes and sending me texts. It feels like a gift each time I get a new message from him. And in true Mexican fashion, the messages are always poetic, always layered. “Como. le. demuestro. mi. amor?”

In his own way, he already has.

*****

It was emotional to listen to him talk with you in the interview. I didn't catch everything he said, but I understood how proud he is of your writing, that was so clear!